CHARLES HARTLEY, Attorney at Law

Personal Photography and Personal Websites:

Issues concerning model releases and self-publishing photographers in the Internet age

By Charles E. Hartley, Esq.1

Affordable digital photography and new opportunities for photographers to widely distribute their work have exposed gaps in California law covering the issue of when permission is required from photographic subjects used for commercial work. Blogs, online forums and online photography galleries allow photographers, amateur and professional, opportunities to share their work with a wider community than ever before. Some photographers may choose a limited audience, regulated by invitation or subscription, with access by password, while others might open their work for all to see, but little concern is given for potential liability to the subjects of those photographs for the use of their likenesses.

This article discusses the rights the people in the photographs (or their owners or guardians) have in regard to the distribution of images in which they appear and exceptions available to photographers to allow for the distribution of their work under California law. More specifically, what rights does a photographer have to post photographs of identifiable people online without their express permission? As of the 2015 update to this article, discussion of Penal Code section 647's recent creation of criminal liability for people, including the original photographers and copyright holders, who "distribute" photographs that include intimate body parts is included at the end of the article.

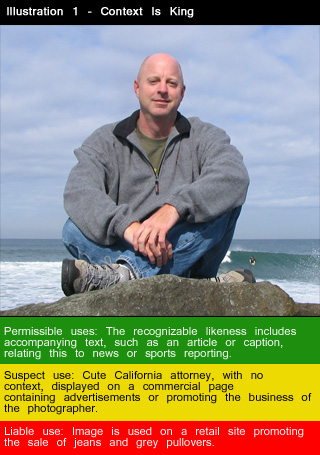

Professional photographers have obtained releases from their models for years. Why? Because under California law, people have the right not to have their likenesses exploited commercially by others. This is now understood to be a proprietary interest. 2 Unless certain legal exceptions such as those for news, public affairs and sports coverage apply, likenesses used commercially must be by permission of the person in the photograph, or the user may be liable for actual or statutory damages starting at $750. A photograph in and of itself is not the problem; how the person's likeness is being used is the act that may create a liability. What matters is context, and the same photograph's use may be quite appropriate in one context and completely inappropriate in another.

Photographers and legal practitioners first need to focus on certain basic questions:

• Is the photograph a likeness of someone recognizable or identifiable?

• Is that person's likeness being used commercially? Is the photograph being sold, or being used to sell something else?

• How closely is the commercial use tied to the subject of the photograph?

• Is the photograph's use protected as news, public affairs or sports coverage?

Discussion of this issue has to begin with the law itself. In addition to some common law causes of action, the California legislature has specified this right in the opening sentence of California Civil Code section 3344.

3344. (a) Any person who knowingly uses another's name, voice, signature, photograph, or likeness, in any manner, on or in products, merchandise, or goods, or for purposes of advertising or selling, or soliciting purchases of, products, merchandise, goods or services, or for purposes of advertising or selling, or soliciting purchases of, products, merchandise, goods or services, without such person's prior consent, or, in the case of a minor, the prior consent of his parent or legal guardian, shall be liable for any damages sustained by the person or persons injured as a result thereof.

This appears all well and good, and probably was when the law was written in 1971, except for the fact that each day in 2015 thousands of likenesses are uploaded to the internet, many presumably without express permission.3 Some of those sites require payment for access, and others are monetized through the sale of advertising (the solicitation of purchases). In some cases photo galleries represent direct advertisements either for sale of prints of the photos or contract work by the exhibiting photographer.

Hypothetically, when an internet user uploads a photo of another person's likeness to a public website, and then allows advertising on the site, the user may be liable for damages under California law for appropriation of one's likeness unless one of the statutory exceptions applies to the image. Those exceptions become more important if the image is used as an advertisement for the site, or admission is charged for the site (placing it 'in the product' of the site).

Exceptions to this code section are made for

(d) For purposes of this section, a use of a name, voice, signature, photograph, or likeness in connection with any news, public affairs, or sports broadcast or account, or any political campaign, shall not constitute a use for which consent is required under subdivision (a). 4

Mainstream media and traditional news outlets use this exception daily for news and sports coverage. Just exactly where other websites might fall under this law has been vague until recently, and is still not completely defined.

The litigation on these questions has been sparse, possibly because the question of damages 5 would generally limit the incentive to pursue a claim through the appellate process, but much of the available case law has focused on defining that middle exception, "public affairs."

Until recently, the leading case to which one could turn to for guidance on this issue was Dora v. Frontline Video. 6 In Dora, the Court of Appeals examined a famous surfer's claim arising from use of his likeness in a documentary film. The subject of the film was surfing in California, and the court held that a topic as important as surfing to California was certainly within the public affairs exception, even if it does not relate to politics or public policy. 7 In the film context, in 1993, the documentary on a topic of interest, maybe not even important, and certainly not related to politics and public policy, was public affairs.

This is consistent with a pre-Internet decision dating from 1962, when the Court of Appeals held that "matters in the public interest" was defined as follows: "The privilege of printing an account of happenings and of enlightening the public as to matters of interest is not restricted to current events; magazines and books, radio and television may legitimately inform and entertain the public with the reproduction of past events, travelogues and biographies." 8

The Dora court did not remove all limits to their definition though; they specifically held that public affairs must be related to real-life occurrences. 9 Using an image in a fictionalized account would be beyond the exception defined by Dora. Protection for a fraudulent news story allegedly planted to increase periodical sales was specifically rejected by the courts in Eastwood10. How these holdings would apply to otherwise protected speech like satire is uncertain.

In May 2006 the California Court of Appeals decided a case (O'Grady v. Superior Court11) that clarified the status of personal websites and their relation to traditional media and productions.

O'Grady does not directly discuss the right of publicity being discussed here, but discusses the relationship of internet posters to the traditional media. In 2004, Apple Computer, Inc., sued several unknown persons who it believed had posted confidential information to various websites. In order to identify the persons they believed had violated confidentiality agreements, Apple subpoenaed the records of the websites. The websites resisted, citing various protections available to newsgatherers under California law. The trial court sided with Apple, opining that public interest (based on site traffic) was not the same as the public interest.12

The Court of Appeals disagreed.

We decline the implicit invitation to embroil ourselves in questions of what constitutes "legitimate journalis[m]." The shield law is intended to protect the gathering and dissemination of news, and that is what petitioners did here. We can think of no workable test or principle that would distinguish "legitimate" from "illegitimate" news. Any attempt by courts to draw such a distinction would imperil a fundamental purpose of the First Amendment, which is to identify the best, most important, and most valuable ideas not by any sociological or economic formula, rule of law, or process of government, but through the rough and tumble competition of the memetic marketplace.13

The central point between Dora and O'Grady appears to be context. When the site in question is making a bona fide attempt to provide information, the O'Grady court seems to be saying that it should be treated as a news or media enterprise, particularly if that is how the publisher holds himself out. This builds on the Dora court's holding that politics or public policy are not essential ingredients to qualify a publication or production as "public affairs." Attempts to document conditions or describe real-life events would certainly seem to be exempt from the permission requirements of Civ. § 3344 under this trend in the case law.

So, what does this mean for the photographer posting their photographs on a personal website? What matters is context.

So, what does this mean for the photographer posting their photographs on a personal website? What matters is context.

• A website that charges for admission to photos of scantily clad Californians, yet provides no context, may have liability issues. This author is not certain captions relating to "big gazoombas" or "nice blank(s)" would be the basis for a satisfactory "public affairs" exemption from the permission of the model required by the law.

• On the other hand, a website collection of photographs showing likenesses taken at a public event could easily be seen as exempt in line with the holdings in Dora and O'Grady. An autobiographical piece, including images of others around the reporting principal such as team photos would seem to fall within the holding of Dora, as would an account of the event illustrated by relevant photos.

• These examples are the clearer ends of a spectrum. There is certainly a line between the two where liability arises, and that line has not yet been completely defined by the courts and the legislature.

Relevant questions for the publisher or legal practitioner advising a publisher are going to include:

• Is the image itself part of the commercial product? Is this a website requiring subscription payments? Does the site sell prints of its images? While important, answers to these questions are not necessarily dispositive. Note that even newspapers are sold, individually or by subscription.

• How closely is the likeness tied to the product advertised? For example, a photograph of a surfer underneath an ad for the publisher's surf school would be closer to the law's intended protections then a photograph of a surfer in the context of comments on beach conditions that happened to carry advertisements placed by third-parties.

• Does the image have context or direct captioning indicating newsworthiness, a sporting event, or an account of an event of public interest? There's no indication that a wide public audience is necessary, just that some members of the public might be interested in the facts.

There are many areas where the codified law has not kept up with the technological changes in the distribution of ideas and artistic expression. This is clearly one of them.

2015 Addendum: Penal Code § 647 now creates criminal liability for any person, including the photographer, who distributes intimate photos that were intended to be kept private with an intention of causing emotional distress. Including amendments that took effect on January 1, 2015, the code section reads:

(j)... (4) (A) Any person who intentionally distributes the image of the intimate body part or parts of another identifiable person, or an image of the person depicted engaged in an act of sexual intercourse, sodomy, oral copulation, sexual penetration, or an image of masturbation by the person depicted or in which the person depicted participates, under circumstances in which the persons agree or understand that the image shall remain private, the person distributing the image knows or should know that distribution of the image will cause serious emotional distress, and the person depicted suffers that distress.14

The code continues by defining distribution at (B) and "intimate body parts at (C).

For purposes of this article, the key element is distribution contrary to an agreement or understanding that the image will remain private. The difference with imagery covered by this new law versus imagery covered by § 3344 is the distributer's intent. Rather than asking whether the image use is intended to be commercial, the question is now whether the use is in violation of an agreement or understanding and intending to cause emotional distress to the image's subject. As with the potential exposure under Civil Code § 3344, risk to the photographer (or distributor) is abated by specific agreement on use of the imagery, such as a model release.

Note is made that this is based on California law, and that the laws of other states or countries may also apply to a particular online venture, and that no article can or should substitute for the professional advice of a licensed legal practitioner in a particular jurisdiction.

Notes

1 Mr. Hartley has been a member of the California Bar since 1999 and moderator/webmaster of beachlaw.info since 2003. A California native, he is a 1999 graduate of the University of Idaho College of Law, and received his B.A. from the University of California at Berkeley in 1986 with a double major in Political Science and Geography. He still practices photography as a hobby and on an occassional free-lance assignment.

2Christoff v. Nestle USA, Inc. (2007)152 Cal.App.4th 1439, 1463, overturned on other grounds. See also Downing v. Abercrombie & Fitch (9th Cir. 2001) 265 F.3d 994, 1004, citing to McCarthy, Rights of Publicity and Privacy section 11.13[C] at 11-72-73(1997).

3 Aside from numerous personal sites, utilizing a variety of software packages and services such as those from blogger.com, and wordpress.org, and photographic gallery software such as ZenPhoto, Gallery, Coppermine, sites such as pinterest.com, tumblr.com and flickr.com are promoted as allowing users to post and "share" photographs online.

4 California Civil Code § 3344

5 From Civ § 3344, "[I]n any action brought under this section, the person who violated the section shall be liable to the injured party or parties in an amount equal to the greater of seven hundred fifty dollars ($750) or the actual damages suffered by him or her as a result of the unauthorized use, and any profits from the unauthorized use that are attributable to the use and are not taken into account in computing the actual damages. In establishing such profits, the injured party or parties are required to present proof only of the gross revenue attributable to such use, and the person who violated this section is required to prove his or her deductible expenses. Punitive damages may also be awarded to the injured party or parties. The prevailing party in any action under this section shall also be entitled to attorney's fees and costs."

6 Dora v. Frontline Video, Inc. (1993, 2nd Dist) 15 Cal App 4th 536.

7 Id.

8 Eastwood v. Superior Court (National Enquirer, Inc.) (1983) 149 Cal.App.3d 409, 421, citations omitted.

9 Dora v. Frontline Video, Inc. (1993, 2nd Dist) 15 Cal App 4th 536.

10 Eastwood v. Superior Court (National Enquirer, Inc.) (1983) 149 Cal.App.3d 409, 426.

11 O'Grady v. Superior Court (Apple Computer, Inc.) (2006) 139 Cal.App.4th 1423.

12 Id., at 1438.

13 Id., at 1457.

14 California Penal Code § 647(j)(4).

This is an original article created for hartley-law.com in August 2006, updated periodically and most recently in January 2015. Please contact the author to discuss reprint rights or custom adaptations for your site, publication or audience.

Mail: 197 Woodland Parkway #104, PMB 403, San Marcos, California 92069

Toll free voice and fax: 888/859-9884

E-mail: charles@hartley-law.com

Copyright 2000-2022 | Disclaimer | Privacy Policy